On the return trip once we had linked up to the Stuart Highway via the Buntine and Buchanan Highways we moved quickly south trying to make up for extra time in taking the northern route from Lajamanu. Our aim was get beyond Tennant Creek so that we could camp overnight in our swags at Karlu Karlu, a series of round boulders, which have formed from an enormous chunk of granite, and which are strewn across a large area of a wide, shallow valley.

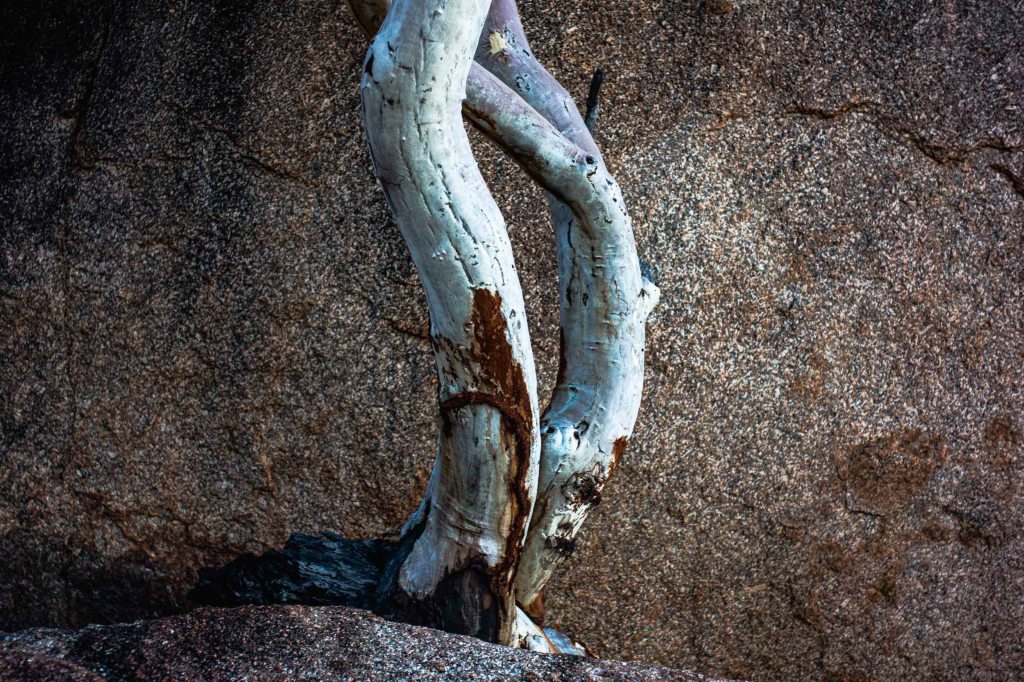

We wanted to photograph the impressive rock formations of huge, red, rounded granite boulders in the early morning light because daylight drains all the colour out of rocks, and flattens the shapes. The next morning, whilst I was photographing the rocks I realised how much my approach to photographing the landscape worked within the common conception of the landscape tradition in which the ‘landscape’ is a pictorial way of representing, and in doing so it is transformed into something useful for human beings.

Thus the colonial photographers on the various expeditions to Alice Springs and beyond were interested in how the land could be useful for development–ie., for the pastoral industry or for agriculture. Karlu Karlu in contemporary postcolonial Australia is an iconic site for the tourism industry, which frames the landscape as something to be viewed and appreciated. Karlu Karlu is right up with Uluru and the Olgas as iconic tourist sites.

According to the common conception the landscape is the product of an essentially representational construal of our relation to the land which involves operation and detachment. In photographing the rocks I, as a photographer, take the landscape to involve the presentation of the world as an object, seen from a certain view, structured , framed and made available to our gaze. These views affect us, but because they have already been seen as views, so they are separated from us, and our involvement with them is based purely in the spectatorial.

This standard conception of the visual or pictorial presentation is one in which we remain as mere observers of the presented scene, with a strong sense of a separation between the viewer and what is viewed in photography, more so than in other modes of presentation.

After being at Lajamanu, the problem that I experienced with this standard conception is the separation bit. I realise that the landscape is about connection as well as separation; connection in the sense of being involved in it and with the modes of life of this place. The area used to be a meeting place for many tribes, with many languages, all of whom shared responsibility for the place--namely the language groups of the Alyawarre, Kayteye, Warumunga and Warlpiri people.

In settler capitalism, for instance, Karlu Karlu was known as Devils Marbles. It was in 2008 that the government handed back ownership of Karlu Karlu to its traditional owners, after a 28-year campaign. Karlu Karlu (in Alyawarre a local Aboriginal language) is now recognised and acknowledged as a sacred site for a number of aboriginal people including the Walpirri.

The tourist aesthetic frames Karlu Karlu as wilderness, and it emphasises the timeless natural to the exclusion of the human avoiding. This is an aesthetic which frames the subject matter through the absence of any reference to the human.

Leave a comment